Berkhout, P., T. Achterbosch, S. van Berkum, H. Dagevos, J. Dengerink, A.P. van Duijn, I. Terluin, 2018. Global implications of the European Food System; A food systems approach. Wageningen, Wageningen Economic Research, Report 2018-051. 56 pp.; 4 fig.; 2 tab.; 73 ref.

The EU is a major player in the world market for agricultural products, both dependent on commodity imports from many countries, and exporting high-value agricultural products. There is a need to better understand the impact – on people, planet and profit – of the EU trade on food systems outside the EU, with a focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC).

The top 5 of imported products by the EU28 from third countries includes fish (mainly fresh salmon and frozen shrimps & prawns), fruits and nuts (bananas and almonds), coffee and tea, residues from the food industry (oil cakes from soy bean meal), and oilseeds (soy bean and rapeseed). (page 15)

The top 5 of exported products by the EU28 to third countries includes beverages (wine and spirits in particular), dairy produce and eggs (cheese), meat (pig meat), cereals (wheat), and cereal preparations (flour); Shares of this top 5 were rather stable in the period 2000-2016 apart from cereal preparations, which increased from 5% in 2000 till 8% in 2016. (page 16)

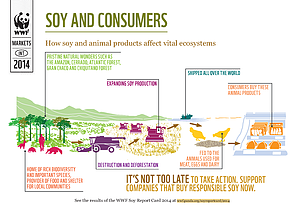

deforestation. Yearly, 3.7m hectares of forests disappear in major soy producing countries Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. Since 2000, the soy cultivation growth area has grown by more than 10% a year in these countries. Monoculture soy production and deforestation both contribute to problems of soil degradation. Moreover, pesticide use in soy production is known to produce adverse health effects in soy producing areas. Soy production is associated with different societal impacts. In the search for new agricultural land for soy cultivation, land conflicts often arise. Soy producers are known to encroach on nature reserves and reserves for indigenous people. Mechanisation of soy production has reduced the employment opportunities in soy production, but has increased the income opportunities for farmers producing soy. Other concerns are raised about the extent to which land converted for soy production can no longer support food crops that are needed to meet the local food demand. (page 21-22)

Member States put an excessive pressure on marine resources, there is an increasing reliance of West Africa’s coastal population on fisheries for their food and income despite decreasing total income and increasing fishing costs, which in turn aggravated poverty. Small-scale fishing in West-Africa is an activity of last resort. Despite the fact that small-scale fishing is not a source of sustainable livelihood, the number of people depending on fisheries is still increasing. Some sceptics link the loss of fisheries livelihoods to conflicts and dislocations on the African continent with migration and its accompanying environmental, economic, social and health & safety issues as a result (page 26)

The brunt of open data in LMIC is geared to support research on agriculture, livelihoods and environmental impact; it covers much less of the perspectives on food processing and transformation, on distribution &and provision, and on increasingly complex behavioural drivers of food choice, habitual diets and nutrition outcomes. The brunt of data on the downstream food systems activities sits with the private sector, in LMIC as well as in the EU. (page 36)

Source: PAEPARD FEED

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by secretary

by admin

by admin

by admin

by admin

by admin

by admin

by admin

by admin

by admin